Reading Time: 12 Minutes 7 Seconds

Historical background

Due to the discovery of coal reserves in Kladno in the 19th century, the town started to receive an increasing number of miners and metal workers.

By the 20th century Kladno has expanded rapidly, creating a severe housing shortage for the workers and their families.

The mines and smelters, which were state-owned at that time, were aware of this problem and in 1946 launched a plan for a new housing development.

The town of Kladno owned some empty plots on its western side, which is the area corresponding to today’s neighborhood Rozdělov.

The ground there was solid and unpolluted, and the wind did not carry fumes from the iron and steel works, so residential construction was permitted.

Prague architect Josef Havlíček, known for housing projects including Dům Radost in Prague, was invited as chief architect.

Other architects contributors included:

- Václav Hilský – Prague architect who collaborated on the layout and housing designs.

- Miroslav Koněrza and Emil Kovařík – architects employed by the mining company, involved in the early design work for the settlement on behalf of the mines.

- Karel Filsak and Karel Bubeniček – architects who led the later overall architectural program.

Havlíček and his team promptly drafted a master plan for the new settlement.

Construction was partially financed by the mines and steelworks and partially by the Ministry of Labour and by UNRRA, an organization tasked with aiding and reconstructing war-torn countries.

The Ministry and UNRRA wanted to test new methods for mass housing construction, so the state announced a program of so-called “model housing estates” to serve as experimental prototypes for future housing development.

Design concept and influences

The project team continued pre‑war architectural traditions and tried to avoid the Sorela (Socialist Realism) style imposed by the commies during those years.

They embraced French modernism, arguing that exterior ornaments would be difficult to maintain, with the consequence that they could deteriorate and fall on people’s head.

The design approach for the new housing estate envisaged a cohesive neighborhood with green spaces, such as parks and playgrounds, and served by public transport. It was supposed to be a model of ideal collective housing.

The district was intended to be largely self-contained, providing all the necessary civic and cultural amenities: schools, a kindergarten, a community centre, markets and shops, a theatre, a hospital, garages and a central heating plant.

In addition, residential areas were to be clearly separated from the industrial zone.

The original layout comprised 64 single‑storey houses, 24 two‑storey houses, 14 three‑storey houses and 5 high‑rise blocks.

The high‑rise buildings (precisely the věžáky) were initially designed with a Y‑shaped plan in a functionalist spirit, inspired by Auguste Perret’s modernist conceptual schemes of reinforced‑concrete skyscrapers for the “Tower Houses“.

Political and stylistic constraints, however, forced repeated redesigns.

Havlíček revised the věžáky to a T‑shaped plan, and at the investors’ request he included an additional tower, bringing the total to six: three for miners and three for steelworkers.

The final scheme accommodated approximately 5,000 residents.

Havlíček’s opposition to the imposed style harmed his career: he tried to diplomatically meander in complicated times, but suffered professionally and was not appointed professor.

Plan and development

Despite a very promising start, only 20 apartment buildings were completed by the end of 1948, two years after the project began.

Harsh weather, material shortages, lack of workers, and organizational chaos among the companies in charge of the construction slowed the works.

In addition, halfway through the project, in 1949, the Ministry of Technology issued a decree requiring more efficient construction methods (to save money).

It ordered mass production of building components, such as the famous prefabricated panels used in the ubiquitous paneláky (panel houses).

The decree applied only to new construction, not to houses already under way, so the věžáky were exempt.

Nevertheless, the development proposal had to be revised once again in 1950 and the family houses intended for the southern section were altered to comply with the new rules.

Of the original plan, only the 6 towers and the department store was completed; the surrounding area was filled with standardized panel residential blocks.

The development had been intended as a model housing estate showcasing ideal collective living, but changes in policy and resources altered that vision.

Ultimately, the first tenants moved in on 20th December 1956 and the rest of flats were fully occupied one year later.

The estate’s official name was never clear, as colloquially different designations were used.

During the Communist era the council approved the name “Sídliště Vítězného února (Victorious February Housing Estate), to commemorate the February 1948 coup that brought the commie party to power.

Such event marked the beginning of four decades of Communist rule in the country, significantly impacting the political landscape of Europe during the Cold War.

That name was abolished in 1991 and nowadays the estate is officially called “Sídliště architekta Havlíčka” (Housing Estate of architect Havlíček).

The complex was declared a cultural monument in 1987.

Architecture of the věžáky

The věžáky became a symbol of modern, comfortable living and they stand among the most significant architectural landmarks of the era, not only in Kladno but across the Czech Republic.

Their distinct design and practical integration with everyday life represent the mid‑20th‑century atmosphere.

Each block is organized into separate wings with an efficient arrangement of living spaces.

Layout and apartments

- Every building offered five flat types (designated with letters from A to E), ranging from studios (about 32 m²) to the largest administrator apartment (about 113 m²) on the first floor.

- The most common units were Type A two‑room flats: two bright rooms, a small kitchen and sanitary facilities, of about 62–66 m², intended for families of four or five people.

- Living rooms face south, while kitchens, bathrooms and toilets are on the northern side.

Flats included extensive built‑in furniture above the standards of the era, making them a luxury. - More than seventy apartments occupy each tower. The allocation was managed by the employer, and obtaining a flat typically meant a major improvement in living conditions (flushing toilets, bathrooms, central heating).

Communal facilities and services

- Each tower featured a spacious entrance hall intended for social gatherings, furnished with sofas, tables and chairs, where residents met to talk, play cards and celebrate.

- Because bathrooms lacked electrical sockets, flats could not accommodate washing machines, so underground laundry and ironing rooms with ingenious drying systems were provided. Use was scheduled via a waiting list, with each family typically having access roughly once every two weeks.

- The terrace on the 11th floor was used for hanging the laundry.

An additional terrace on the top floor, known as the “sun terrace” and protected by high railings, served for recreation: tenants sunbathed here and children played. - Other facilities included three elevators (original wooden ones, later replaced), a cellar for each flat, a room for the building administration, and an underground civil defense shelter.

From 1952, shelters were required in every large capacity apartment building, and had to be equipped according to official guidelines. - An intended waste incinerator never entered into operation, after tests showed fumes leaking into the common areas.

Věžáky – the museum

The creation of a museum that could tell the story of Havlíček’s big architectural project was initiated by the Kladno based association Halda, specifically by Roman Hájek and Alexandr Němec.

Kladno City Hall backed the idea and financially covered the costs of the renovation and propagation campaign.

The museum occupies the first of the six towers, which is still inhabited by several residents, and lets visitors walk the building from the cellar to the roof.

Don’t let the building’s neglected exterior deter you! The interiors will surely impress you.

The věžák can be visited through guided tours of about 1.5 hours, which take place every Saturday and are run by volunteers.

All the relevant information is contained at the official site of the věžáky museum – you can send them an email for options in English.

The tour comprises of five parts: the restored entrance hall, an exhibition in the basement, the civil defense shelter, a model apartment, and a rooftop terrace.

Entrance hall

Excursions start in the entrance hall, a generous area of 100m² that showcases larch paneled walls, red leatherette sofas, large windows, lots of plants, and elegant lighting.

Exhibitions

The tour continues to a renovated room in the first basement (the one intended for the waste incinerator) that today hosts an exhibition about the history and the development of the area.

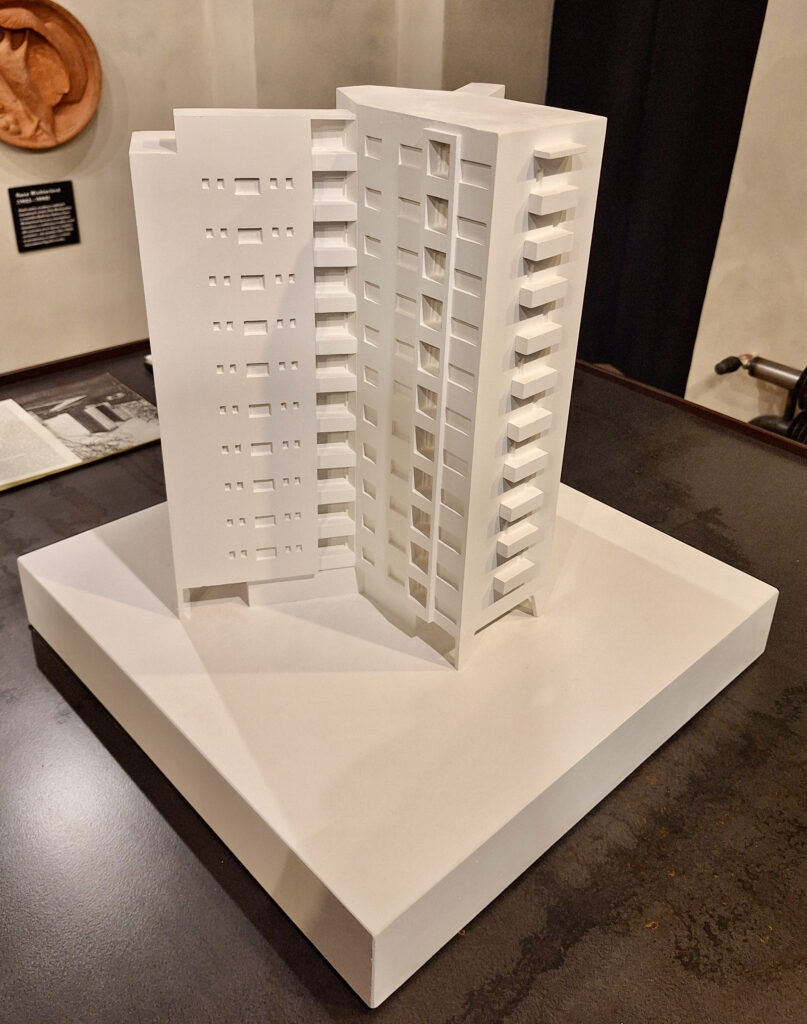

Visitors will watch a short documentary about the collective housing project and roam through displayed models: a wooden reproduction of the housing estate (the whole Rozdělov neighborhood), the plaster casts of Havlíček prototypes of the věžáky (both the original and the adapted one), and a lego representation of the tower building.

Lower basement

One level down are the shelter and a common room that houses functional washing machines and dryers, still used to these days by some residents. This last room is usually not shown.

Typical apartment in the věžáky

Next phase of the tour is the visit to the model apartment, located on the sixth floor.

The authors of the exposition hesitated between whether to furnish the interior of the flat with objects of the era and create a museum-like atmosphere or whether to leave the space clean and let the architecture stand out.

The result is a compromise: the apartment was first furnished in detail, then photographed and ultimately almost emptied. Those photos now hang in large format in the bedroom and living room, and only the basic furniture remains.

The last place to visit is the roof terrace, accessible via steep stairs from the top floor.

The terrace offers a view over the Středohoří (Central Bohemian Highlands), the Jizera mountain range and Říp, as well as over the other buildings of the estate.

Unfortunately, the panorama is not 360°, mostly because of a defense observatory built over the elevator machine roof, whose function has always remained unclear. In addition, high railings, and antennas contribute to block the sight.

Exterior entrance decoration

Adding few decorations on the entrance would give the huge towers a human dimension.

Therefore, it was proposed to add a pair of ceramic sculptures to each věžák, one at each side of the main entrance.

The overcall concept of the ceramic pieces, all representing animals, was to recall the popular use of maiolica during the Renaissance as ornamental touch.

All the 12 circular plaques were products of Czech artists.

The 1st tower, which is where the museum is located, holds two ceramic by Marta Jirásková, Havlíček’s wife: a dog and a cat.

A rooster and a turkey, from sculptor Břetislav Benda, decorate the 2nd tower.

A squirrel and a weasel by sculptor Mary Duras are hanging on the entrance wall of the 3rd tower, while the 4th tower shows an eagle and an owl by Martin Reiner

The 5th tower displays a ram and a sheep by professor Bedřich Stefan, the only pieces without glaze, and Hana Wichterlová depicted a swan and a heron for the 6th tower.